A press conference turns combative

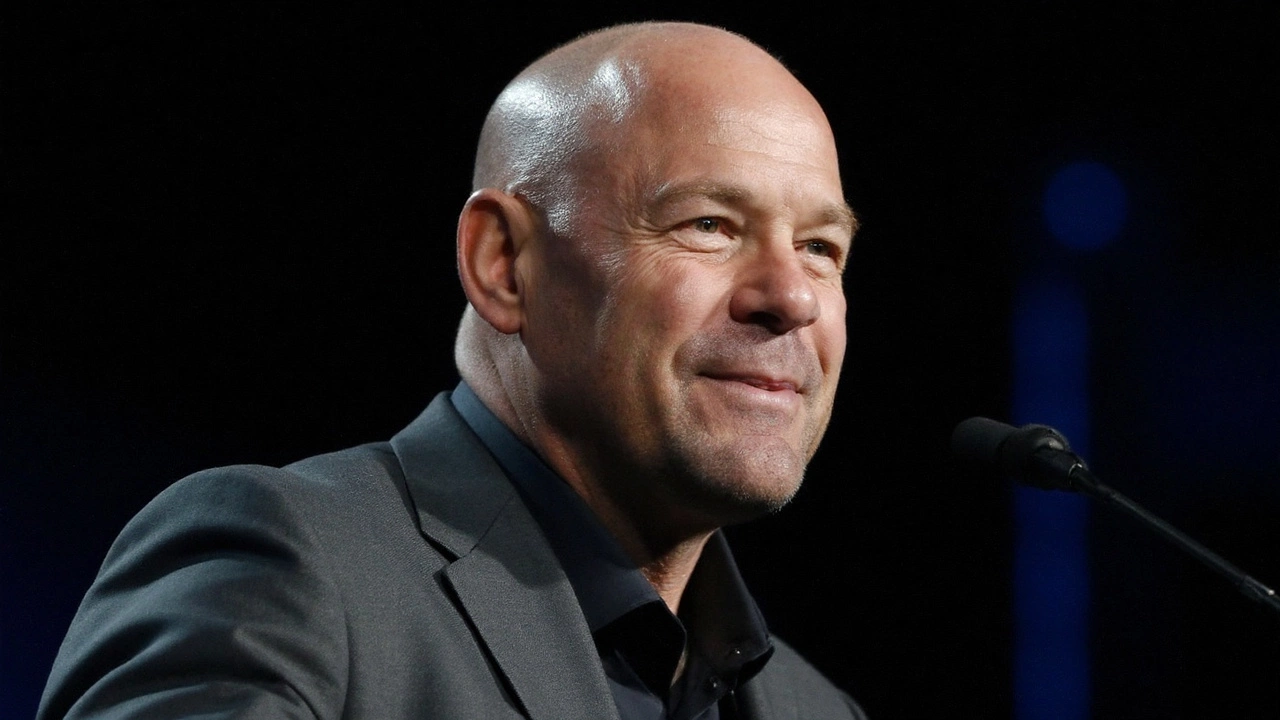

The Canelo Alvarez vs Terence Crawford press conference in Las Vegas briefly stopped being about feints, footwork, and fight-night hype. It became a flashpoint over how boxing is run—and who gets to shape it. When veteran reporter Sean Zittel asked UFC president Dana White about efforts to change the Muhammad Ali Act, White bristled, cut him off, and told him to take it offline. The exchange was tense enough to hush the room.

Zittel set the scene with money. He noted Saturday’s event is tracking as one of the biggest gates in combat sports history and pointed out that the top gates over the last decade have come from boxing. Then he asked why White, whose company has already paid hundreds of millions to settle antitrust lawsuits and still faces two class-action cases, wants to loosen a federal law designed to protect fighters.

White wanted none of it in public. He called the topic a long discussion, told Zittel to set up a private interview, and stressed the presser was about the fighters, not him. When Zittel tried to follow up—citing a recent California State Athletic Commission hearing that mentioned TKO’s proposed amendments—White cut in, accused him of showboating, and said if he wanted to make a scene, they could do it privately. The message was clear: not here, not now.

The optics landed differently depending on where you sit. For some in the room, it looked like a promoter protecting his event from a regulatory food fight. For others, it felt like a power player deflecting a policy question that goes to the core of how fighters get paid and how matchups get made.

All of this unfolded on the week Saul “Canelo” Alvarez, 35, defends his WBA (Super), WBC, WBO, and IBF super‑middleweight titles against Terence Crawford, 37, at Allegiant Stadium. It’s the kind of glove‑touch meeting boxing fans beg for—pound‑for‑pound royalty crossing eras and divisions—now sharing oxygen with a high‑stakes debate over the sport’s rules.

What’s at stake with the Ali Act fight?

Passed in 2000, the Muhammad Ali Boxing Reform Act is federal law built to protect boxers from the worst conflicts of interest and backroom dealing. It requires promoters and sanctioning bodies to disclose key financials to fighters, bans promoters from acting as managers, and demands objective ranking criteria from sanctioning bodies. It tries to keep the business side from steering outcomes in the ring.

That wall is why boxing promoters don’t run their own world titles. Belts sit with sanctioning bodies—WBA, WBC, IBF, WBO—which have their own rankings and rules. Fighters, their managers, and promoters negotiate within that framework. Flawed? Of course—mandatory challengers, sanctioning fees, and fractured titles inspire weekly headaches—but the structure keeps promoter power from swallowing the entire ecosystem.

MMA lives on a different planet. The UFC’s model blends league, promoter, and belt‑maker under one roof. Titles, rankings, and matchmaking live inside the same house, guided by exclusive contracts and clauses that keep talent tied up. That setup would run afoul of boxing’s federal rules, which is why the Ali Act has never applied to MMA. Attempts to expand it to mixed martial arts have been floated in Congress multiple times over the past decade and stalled each time.

What Zittel referenced—loud enough to agitate White—is a push being discussed in and around state forums to reframe how boxing can be organized. A proposal dubbed the Muhammad Ali “Revival” concept would allow “unified boxing organizations,” opening the door for a company to promote fights and run its own championship structure. In plain terms: a promoter‑league model, closer to how the UFC operates.

If that happened, the ripple effects would be huge. Titles could be centralized under a single brand. Rankings might be set by that brand instead of independent sanctioning bodies. Mandatory defenses and eliminators—the machinery that nudges contenders into title shots—could become internal calls. You can imagine the upside touted by promoters: fewer politics, easier scheduling, one set of belts fans can actually follow, and potentially lower friction costs without multiple sanctioning fees.

The tradeoffs are just as obvious. Fighter leverage tends to shrink when one entity controls matchmaking, titles, and rankings. The disclosures required by federal law could be rewritten or weakened if Congress changed the statute. Independent ranking pressure—that outside force that occasionally pries open title opportunities—would fade. And if you’re a contender without a sponsor seat at the house table, your path could depend on executive preference rather than a transparent ladder.

There’s another shadow hanging over the debate: antitrust litigation. White’s company has already paid out roughly $375 million across cases challenging how it controlled the fighter market, with two more class‑action suits still pending. Those cases argued that long, restrictive agreements and a web of contractual tools—like automatic extensions tied to championships—boxed fighters into take‑it‑or‑leave‑it deals and kept pay below what a competitive market would deliver. Whether you agree with that framing or not, it’s the context for why a press‑room question about loosening federal guardrails hit a nerve.

So why push for change at all? The business case writes itself. A single organization coordinating belts and rankings can move faster, stack cards, and keep stars fighting more often without weeks of cross‑promoter haggling. It can bundle TV rights, sponsorships, and global sites into bigger, cleaner packages. It can spotlight rising talent without paying four sanctioning bodies along the way. Fans don’t love alphabet soup; promoters don’t love paying for it.

But the sport’s current structure has its own hard logic. Boxing’s biggest gates and paydays have happened under the Ali Act‑era rules. The reporter’s point at the presser—that the top‑end money is flowing—wasn’t a throwaway line. The Canelo‑Crawford show is on track to become one of the most lucrative live gates in the sport’s history. If the system is minting nights this big, the reform argument flips: fix what’s broken at the margins, not the core that delivers the spectacle.

That’s where the California State Athletic Commission comes in. CSAC can’t change federal law. But it convenes stakeholders, hears testimony, and signals where state regulators stand on proposals that could reshape fighter protections. Zittel referenced a recent CSAC hearing where amendments were discussed in public. For fighters and managers, getting concerns on the record matters; for promoters, so does keeping momentum with regulators ahead of any federal action. White’s choice to deflect at the podium was a reminder: policy battles can wait until the cameras point somewhere else.

Meanwhile, the fight week machinery churns. Allegiant Stadium offers scale rare for a boxing event, with a configuration that can push well past typical arena capacity. Site fees, premium seating, and club‑level hospitality elevate the live‑gate potential. Pay‑per‑view pricing and global distribution round out the revenue stack. In that pile of revenue, the Ali Act’s disclosure rules typically ensure fighters see the math—itemized costs, broadcast deals, and how net proceeds are calculated. If a revival model ever replaced that framework, expect a fresh argument over who gets to open the books and when.

It’s also worth separating two problems that fans often conflate. One: fragmented belts and stalled mandatories that make some matchups maddening to make. Two: fighter leverage and pay, which depend on how concentrated the promotion landscape is. A unified league‑style model might solve the first by brute force while worsening the second. The status quo often does the opposite—more leverage at the top, more chaos in the middle, and patience‑testing politics for everyone.

Back at the dais, White framed the moment as a timing issue. Saturday, he said, is about two fighters, not policy. Fair enough. But the blow‑up ensured policy followed the fighters anyway. Canelo, a unified champion used to navigating sanctioning bodies and mandatories, embodies the current system’s strengths. Crawford, a generational technician who chased legacy across divisions, is the example purists cite when they argue the sport can deliver when it matters. Both are reminders that boxing, for all its messy governance, still produces the nights that make everything else feel trivial.

Yet this part isn’t trivial. If promoter‑run titles become legal, boxing’s power center moves. Sanctioning bodies lose leverage. Managers lose a statutory shield against promoter overreach. Fighters might gain schedule certainty and lose negotiating muscle. Broadcasters would love the programming consistency; independents would hate the gatekeeping. The sport would look more like a league and less like a marketplace.

That’s the substance behind a few clipped sentences at a press conference. The question wasn’t about a one‑off policy tweak; it was about who holds the keys to boxing’s future. And while no rule will change before the first bell at Allegiant Stadium, the week made one thing clear: the battle to rewrite how boxing is governed is moving from backrooms to microphones. The next round won’t be fought under bright lights, but it will decide who gets to make them shine.